Resilience Dividends: Breaking the Nexus of Poverty, Inequality and Climate Risk

The ESCAP Asia-Pacific SDG Progress Report 2024 flagged the region’s regression on SDG 13, climate action. To reverse this trend, it is imperative that both mitigation and adaptation go hand in hand to accelerate climate action. Adaptation measures must protect the lives and livelihoods of the most vulnerable amid the increasing climate change-fuelled disaster risk.

In 2023, the global temperature warmed by 1.5° Celsius above the nineteenth century benchmark. This warming trend is likely to continue, leading to an irreversible widening of the risk and resilience gaps unless climate action is accelerated. It is important to recognize that the risk from warming is global, but adaptation is always local, and resilience is specific to the people, community and ecosystem.

Who bears the brunt of regressing climate action?

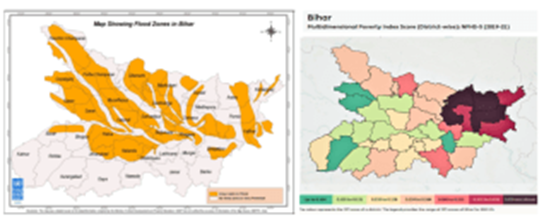

India’s 2021 National Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) baseline report not only sheds light on “how many are poor” but “how poor are the poor.” The report identifies Bihar State as having the highest percentage of population who are multidimensionally poor in India. Of Bihar's population of 130 million, 33.7 per cent live below the poverty line (in 2011), and as many as 52.5 per cent suffer from multidimensional poverty (2015-2016). A loss of one dollar causes their consumption to decrease by 60 per cent, affecting spending on essentials and causing a rippling effect on inequality. The disproportionate impact of disasters on the poor has been one of the reasons behind Bihar’s multi-dimensional poverty. As can be seen in Figure 1, the lowest values of the MPI largely coincide Bihar’s perennially flood-prone districts.

Figure 1. Flood zones vis-à-vis multi-dimensional poverty index of Bihar (Source: UNDP/Niti Aayog and OCHA Relief Web. The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.)

Bihar’s lowest composite MPI score (52 out of 100) is also the lowest among all states of India. Frequent disasters contribute significantly to Bihar’s low scores on SDGs, and the lowest is climate action (16), followed by hunger (31) and poverty (32). This clearly indicates a nexus among disaster fueled by climate change, hunger and poverty in Bihar.

The economy grows but risk outpaces resilience.

Even though the poverty rate in Bihar is much higher than the national average, the state’s economic growth rate has been above the national average, at 10.5 per cent in 2019-2020. Further, Bihar has pulled around 7 per cent of its population out of multidimensional poverty between 2019-2021 and 2022-2023. However, Bihar’s low SDG scores related to climate action, hunger and poverty vis-à-vis high economic growth reveals how risk is outpacing resilience. There is a need to decouple economic development from the increasing risk and vulnerabilities of communities.

At the community level, loss and damage associated with floods in Bihar is pervasive. The government provides compensation to flood-affected households, assisting them to maintain their consumption level. However, the loss of livelihood and diseases faced by households during and after floods are not covered by the compensation. Policymakers must think beyond compensation and seek solutions to safeguard communities from the increasing number of flood events.

Pathways towards averting, minimizing and addressing loss and damage for communities at risk

Targeted policy actions: The Bihar Road Map for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 aims to reduce disaster-related deaths by 75 per cent by 2030. The road map consists of five pillars of which one, the Resilient Village Plans, establishes an operational framework for integrating climate change and disaster resilience in the village development planning in perennially flood-prone areas.

People-centered early warning: Multi-hazard early warning systems are cost-effective ways of protecting people and assets, providing a tenfold return on investment. Bihar’s floods often originate from transboundary river basins. The floods are often caused by unusually heavy rainfall in neighboring Nepal causing about half a dozen rivers flowing through the state to swell. An effective flood early warning system requires a regional transboundary approach that covers the lower reaches of a large geographical area and population.

Nature-based solutions (NbS) are key to ecosystem-based adaptation as they sustainably manage, protect and restore the degraded environment and reduce disaster risk. Around 40 per cent of climate action can be achieved through NbS. It is important to promote conservation of natural ecosystems to mitigate the challenges posed by climate change. A landscape-based approach is desirable for the conservation of waterbodies and linked catchments.

Loss and damage fund (LDF): The LDF set up at COP28 addresses loss and damage caused by slow-onset events and extreme weather events. India’s active engagements in exploring L&D fund could help to support at risk communities. For example, the use of the Aadhaar digital identification system can ensure that funds are directly transferred to the targeted beneficiaries. The LDF could be an instrument of climate justice if it is integrated with adaptation and resilience at grassroots community level and lead to averting, minimizing and addressing loss and damage from climate change.

Localizing SDGs in multi-hazard risk hotspots is key to addressing the nexus of multidimensional poverty, food insecurity and inequalities. It is an entry point for a just transition to climate change adaptation.

By:

Sanjay Srivastava, Chief, Disaster Risk Reduction at UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP).

Shiraz A Wajih, President of Gorakhpur Environment Action Group

The views and opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI).